Why Array

The Right Care for You

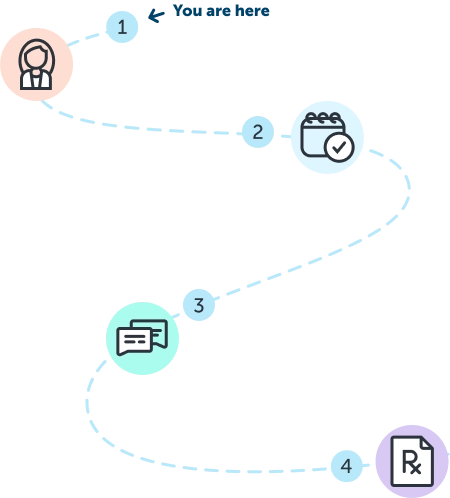

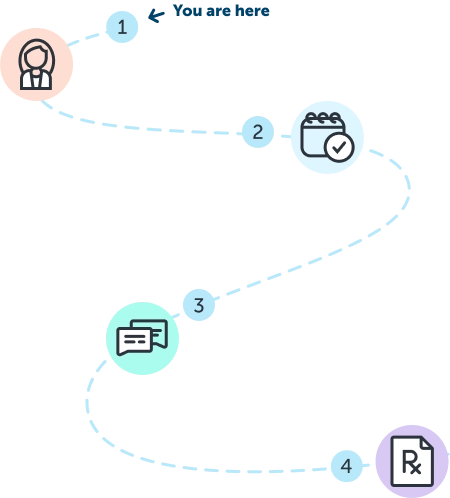

How it works

1Find the Right Clinician for You

Use our provider finder to explore clinicians licensed in your state who accept your insurance. You can search by specialty and expertise to find the one that feels right for you.

2Schedule Your First Appointment

Once you have found a clinician, book your first appointment at a time that works for you. We offer appointments 7 days a week, including evenings and weekends, so care fits into your schedule.

3Start with a Comprehensive Intake and Assessment

During your first session, your clinician will take time to understand your symptoms, history, and goals. From there, we’ll work with you to develop a care plan tailored to your unique needs, using one of our specialized care paths to ensure you receive the right care, at the right time, with the right level of support.

4Ongoing Support and Care Adjustments

Your care shouldn’t stay the same, because your needs change over time – and so will we. Whether that means adjusting how often you meet with your clinician, adding therapy to your care plan, or incorporating medication, we’ll make sure you always have the right support to help you reach your goals.

We’re here to support you. If you have any questions or need help booking your first appointment, please contact our Care Navigation Team at 800.442.8938

What You Can Expect

Why Choose Array Behavioral Care

We know there are many options for mental health care and finding the right provider is important.

At Array, we offer high-quality mental health support tailored to your unique needs. Trust our

experienced professionals to provide therapy and psychiatric care with compassion and expertise.

Personalized Care Paths for Your Needs

At Array, we tailor your care to meet your specific needs. Our custom care paths ensure you receive the right care, at the right time, with the right level of support – no matter where you are on your mental health journey.

Ongoing Guidance and Support

Our Care Navigation and Coordination Team is here to guide you throughout your journey. Whether you need help finding the right clinician, booking appointments, or staying on track with your care, we make sure you have the resources and support you need to reach your goals.

Convenient Appointments on Your Schedule

We know life is busy, so we offer appointments 7 days a week, including evenings and weekends. You can connect with your clinician from the comfort of home at a time that works for you.

Experienced and Compassionate Clinicians

Our licensed clinicians are experts in a wide range of specialties, committed to delivering high-quality care with empathy and understanding. Whether you need therapy or help starting or managing medications, our team is here to provide the right care to help you feel your best.

Secure and Confidential Care

Your privacy matters to us. From your sessions to your health records and payment information, everything is protected and kept confidential through our secure platform, giving you peace of mind while receiving the care you need.

Accessible and Inclusive Services

At Array, we believe care should be accessible to everyone. We offer services in multiple languages and strive to provide culturally competent care, so you feel understood and supported.

Common Conditions

What We Treat

Our diverse and experienced team of clinicians provides compassionate care tailored to you. We treat a wide range of mental health conditions, including:

- Anxiety

- Depression

- Trauma and PTSD

- Grief and loss

- Gender identity issues

- Mood disorders

- Personality disorders

- Psychotic disorders

- Relationship issues

- Sleep disturbances

- And more!

Types of Care

Understanding Your

Care Options

We offer two primary types of mental health care – therapy and psychiatry. Therapy provides emotional support, helps you develop coping skills, and focuses on personal growth, while psychiatry involves diagnosing mental health conditions and prescribing medication when needed. In many cases, a combination of therapy and medication offers the best outcomes. If you’re unsure which option is right for you, don’t worry – our clinicians will guide you to the care that fits your needs.

Learn more about the difference between therapy and psychiatry, the roles of therapists and psychiatrists, and how to choose the right care option for you.

Insurance And Coverage

We've Got You Covered

Array Behavioral Care offers services across all 50 states and Washington, D.C., and we are in-network with most major health plans. We also offer self-pay options for those who prefer to pay out-of-pocket. If you have questions about coverage or payment, our team is here to help guide you through the process.

Insurance Coverage

Check if we’re in-network with your health plan and explore coverage by state.

Billing and Fees

Find details on self-pay rates and costs for different appointment types.

View Billing and Fees

Billing Policies

Learn about our policies for no-shows, late cancellations, and more.

View Billing Policies

What Our Patients Say

Highly Rated by Patients, Trusted for Care

Our patients consistently share positive feedback about their experience with Array. In fact, most say they would recommend our services to others – a reflection of the high-quality care, compassion, and support they receive throughout their journey with us.